Let's build a tool-using agent

giving hands to the brain in a vat

Posted by ekr on 06 Mar 2026

At this point, if you haven't heard about "agentic AI", you haven't just been living under a rock but under a huge pile of rocks. However, even you have heard of agentic AI, you may also have only some idea of what it actually means. If so, you've come to the right place. In this post we're going to build a simple tool-using AI agent and try to get some sense of what it's actually doing.

Here's a typical definition of agentic AI, from IBM:

Agentic AI builds on generative AI (gen AI) techniques by using large language models (LLMs) to function in dynamic environments. While generative models focus on creating content based on learned patterns, agentic AI extends this capability by applying generative outputs toward specific goals. A generative AI model like OpenAI’s ChatGPT might produce text, images or code, but an agentic AI system can use that generated content to complete complex tasks autonomously by calling external tools. Agents can, for example, not only tell you the best time to climb Mt. Everest given your work schedule, it can also book you a flight and a hotel.

In other words, agentic AI doesn't just talk to you but can have side effects in the real world. For instance, you might ask it to book travel for you, do some web searching, send emails, etc. The interesting question here is how.

The first thing to understand is that a large language model (LLM) is what it says on the tin: a language model, which means that it operates at the level of text. At a high level, an LLM takes in a string of text (the prompt) and then emits some other text (the response). It's common to talk about this as an autocomplete or predictive system where the LLM emits the most likely text to come after the prompt, but for our purposes, it doesn't matter: the important thing is that the LLM just manipulates text. Everything we're going to do in this post is downstream of that fact.

Preliminaries #

AI models can either be local (running on your machine or a machine you control) or hosted (running on infrastructure operated by the model provider). In general, the hosted models are a lot more capable and require a lot of compute power, but you can still get fairly far with a local model if you just want to do simple stuff. In a local model, you can provide input to the model directly, but for a hosted model you need to use some interface provided by the model provider. For interactive use, this is often some kind of chat interface, such as ChatGPT, but for programmatic use model providers give you some kind of HTTP API. These APIs are conceptually similar but subtly different, so you need to write your app slightly differently for each platform.

Although you can access local models directly as a practical matter what's convenient is to use something like Ollama, which is an engine that allows you to run a large number of models—and actually knows how to automatically download[1] them—and also provides a common HTTP API which you can use just as you would a model provider's API. We'll be writing our examples using Ollama so that they can work with local models—thus allowing us to do some internal instrumentation—but Ollama can also bridge to the APIs for big model providers, so we can use the same code with Gemini, Claude, etc, allowing us to demonstrate things with better models.

In practice, you would usually not talk to the HTTP API directly, but instead download some local library (e.g., ollama-js) which takes care of the HTTP API mechanics. In this case, however, I want to be able to show what's actually happening, so we're going to be writing to the API directly, using the built-in nodejs fetch API. To do this, we're going to have a trivial JS API client, shown below.

import fetch from "node-fetch";

const server_url = "http://localhost:11434";

const g_chat_url = `${server_url}/api/chat`;

const g_model = process.env.AGENT_MODEL || "mistral-small";

export async function ChatApi({

endpoint_url = g_chat_url,

model = g_model,

tools = [],

} = {}) {

const verbose = !!process.env.VERBOSE;

async function complete(messages) {

const body = {

model: model,

stream: false,

tools,

messages,

};

if (verbose) {

console.log("REQUEST:", JSON.stringify(body, null, 2));

}

const response = await fetch(endpoint_url, {

method: "POST",

body: JSON.stringify(body),

});

const json = await response.json();

if (verbose) {

console.log("RESPONSE:", JSON.stringify(json, null, 2));

}

return json.message;

}

return {

complete,

};

}A Simple Chatbot #

We're going to warm up by build a simple chatbot, which is comparatively trivial [2] given this kind of model. We just need to connecting it up some interface that reads text from the user and sends it to the model, as shown in the diagram below.

We can then write a trivial chatbot like so.

import { ChatApi } from "./api.js";

import { Chat } from "./chat-framework.js";

const api = await ChatApi();

async function handler(line) {

const result = await api.complete([{ role: "user", content: line }]);

return result.content;

}

Chat(handler);Note that this code makes use of a chat framework[3] that just loops around input and passes the results to the handler function shown here. This lets us handle stuff like reading from the terminal and/or opening the input all in one place so you can focus on the main code.

Anyway, here's an example interaction.

>>> Hello

Hello! How can I assist you today?So far so good, but now try to have a conversation. For example:

>>> My shirt is blue

That's a nice color! Do you need help with something related to your shirt, or would you like to talk about something else?

>>> What color is my shirt?

I don't have the ability to see or know what you're wearing right now. Could you please provide more context or clarify your question?WTF? I just told you the color of my shirt.

What's going on is that the model itself

is stateless: it just takes in a string of input and produces

output, so as far as the model is concerned when I asked about my

shirt color, this is the first thing I said.

If we want to have a conversation,

I actually need to play back the entire conversation

with each request to the API. We do this by keeping a context variable which

is just the list of all the things that we've said to the

LLM as well as the things it said back to us, as seen in:

import { ChatApi } from "./api.js";

import { Chat } from "./chat-framework.js";

let context = [];

const api = await ChatApi();

async function handler(line) {

context.push({ role: "user", content: line });

const result = await api.complete(context);

context.push(result);

return result.content;

}

Chat(handler);You'll notice that each entry in the context contains

a role parameter, which helps the model keep straight

who said what. Now when we run this, we get the right answer.

>>> My shirt is blue

That's a nice color! Do you need help with something related to your shirt, or would you like to talk about something else?

>>> What color is my shirt?

You told me that your shirt is blue. Is there anything specific you would like to know or do regarding your shirt?Congratulations, we now have a primitive but functional chatbot.

Tool calling #

What we've built so far is just a brain in a vat: we can feed it text and it responds with other text, but it can't do anything that has side effects. That's all great, but the examples we gave above (booking travel, etc.) require the ability to do things out in the world—or at least on the Internet—so we need to enable that somehow. The way this is done is by giving the LLM something called a "tool". LLM tools are kind of like API calls in traditional programming languages: they are functions that let the LLM do something.

Using tools with an LLM is conceptually simple:

-

The wrapper code tells the LLM about the tool by adding the tool definition to the context.

-

The LLM invokes the tool by putting tool-specific instructions in the output.

-

The wrapper code detects the tool-specific instructions in the output and invokes the tool.

-

The wrapper code takes the tool result and passes it to the LLM as part of the context.

Tool Definitions #

The tool definition is basically just a JSON expression, like so:

{

name: "read_temperature",

parameters: {

type: "object",

properties: {

location: {

type: "string",

description: "The room name",

},

},

required: ["location"],

},

description: "Return the room temperature in degrees Celsius",

}This should be reasonably self-explanatory, but just in case:

name:- The name of the tool itself (in this case

print_message). description:- A text description of the tool's behavior

parameters:- The arguments to the tool

Think about the tool definition as API documentation for the

LLM: it tells it about the tool, what it does, and how to

call it. The description field is just freeform text

which is assimilated by the model. The easiest way to think

about this is that the LLM reads the documentation just like

a programmer would and then picks the right tool(s) for the

job based on your instructions.

Model Calls Tool #

In order to call the tool, the model provides a response that has the information about the tool to call text. For instance:

{

"id": "call_5wrxuo5r",

"function": {

"index": 0,

"name": "read_temperature",

"arguments": {

"location": "living room"

}

}

}This says exactly what you think it says, namely "I would like to call the

tool get_temperature with the location argument being

living_room But of course,

this doesn't have any effect on its own; it's just some text the model

spits out that is asking the agent wrapper to call the tool.

Tool Execution #

The way that the tool actually gets called is that the wrapper code detects that the model's output is actually a tool call and calls the tool rather than printing the output (or whatever it would ordinarily do with it). In other words, you need to update the agent wrapper code to be something like this:

import { ChatApi } from "./api.js";

import { Chat } from "./chat-framework.js";

import { Tools } from "./tools.js";

let context = [];

function call_tool(call) {

if (Tools.implementations[call.name]) {

console.log(

`+++ Calling tool '${call.name}' with arguments ${JSON.stringify(call.arguments)}`,

);

const result = Tools.implementations[call.name](call.arguments);

console.log(`--> ${JSON.stringify(result)}`);

return result;

} else {

throw new Error(`Missing tool ${call.name}`);

}

}

const api = await ChatApi({ tools: Tools.definitions });

async function handler(line) {

context.push({ role: "user", content: line });

let response = null;

for (;;) {

response = await api.complete(context);

if (!response.tool_calls?.length) {

break;

}

context.push(response.tool_calls[0]);

const tool_result = call_tool(response.tool_calls[0]["function"]);

context.push({

role: "tool",

id: response.tool_calls[0].id,

content: tool_result,

});

}

context.push(response);

return response.content;

}

Chat(handler);This code is comparatively simple, but let's work through it in pieces. Whenever we send a request to the model API, we can get one of two responses:

- The response can contain a text response (the

messagesfield is populated.) - The response can contain a tool call (the

tool_callsfield is populated.)

In the first case, we just display the response to the user and then read the user's next input, just as with our original chatbot code.

What's new here is the tool call request. In this case, we don't want to display the result to the user, but instead intercept the response and call the appropriate tool. Handily, the tools are named, so we can just look up the appropriate implementation by name and call it. Once we have the response, we can add it to the context and call the completion API again. Here's a simple exchange:

User> Use the available tools to find out the current temperature.

+++ Calling tool 'read_temperature' with arguments {"location":"living room"}

--> "25"

Agent> The current temperature is 25°C.If you look closely, you'll notice something interesting. I never told the model which room I wanted it to get the temperature for; it just hallucinated "living room". This behavior is actually nondeterministic and model dependent (I'm using (mistral-small.) Some fraction of the time, the model actually refuses to give me an answer and instead asks what room I want:

User> Use the available tools to find out the current temperature.

Agent> Sure, I can help with that. Could you please specify which room's temperature you would like to know?Providing the response works exactly as you'd expect, with our agent providing the following context:

[

{

"role": "user",

"content": "Use the available tools to find out the current temperature."

},

{

"id": "call_5wrxuo5r",

"function": {

"index": 0,

"name": "read_temperature",

"arguments": {

"location": "living room"

}

}

},

{

"role": "tool",

"id": "call_5wrxuo5r",

"content": "25"

}

]As you can see, the context here includes everything that has happened so far, namely:

- My request for temperature

- The tool call request from the agent

- The response from the tool

Just as before, the model is stateless, so if we don't remind it that it called a tool, it doesn't have any context for what the answer "25" is.

The key point here is that all the tool action happens in the wrapper

code. The LLM has no idea how the tool works; it just knows whatever

the wrapper told it about what each tool does and then whatever the

wrapper says the tool did. And in fact, my implementation of get_temperature

isn't attached to a thermometer or some kind of temperature API and

doesn't have any idea what the temperature is, it's just returning

the fixed value 25.

Notice also that the agent wrapper doesn't

really know anything about the tools either, it's just importing

the list of tools from tools.js, passing the descriptions to

the model and invoking the appropriate tool. All you need to do

to add another tool is add it tools.js.

Multi-Round Tool Execution #

Our wrapper code will keep looping until the model returns some response, so this means we can have multiple rounds of tool execution. So, for instance, we can have a simple thermostat which turns on the heat if we are below some target temperature.

To do this, we first need to give the model a new turn_on_heat tool.

{

name: "turn_on_heat",

parameters: {

type: "object",

properties: {

location: {

type: "string",

description: "The room name",

},

},

required: ["location"],

},

description: "Turn on the heat",

},

}This is implemented as:

turn_on_heat: () => {

{

return "The heat is now on";

}

}Then with the right instructions...

User> Use the available tools to find out the current temperature in the living room and use the right tool to turn on the heat if it is under 40 Celsius.

+++ Calling tool 'read_temperature' with arguments {"location":"living room"}

--> "25"

+++ Calling tool 'turn_on_heat' with arguments {}

--> "The heat is now on"

Agent> The current temperature in the living room is 25°C, which is below 40°C. I have turned on the heat for you.You might notice that my instructions here are pretty verbose, and in particular that I'm telling it to use the tool to turn on the heat. What's going on here is that I'm fighting with the model: mistral-small only has about 20B parameters and so it's not really smart enough to figure things out if you're not super explicit. Here's what happened if I didn't tell it that it had a tool to turn on the heat:

User> Use the available tools to find out the current temperature in the living room and turn on the heat if it is under 40 Celsius.

+++ Calling tool 'read_temperature' with arguments {"location":"living room"}

--> "25"

Agent> I don't have access to real-time data or the ability to control physical devices like thermostats. However, I can guide you through the process of checking the temperature and turning on the heat.

To check the current temperature in your living room:

1. Use a thermometer placed in the living room.

2. Check the reading on any smart home device that monitors temperature if available.

If the temperature is below 40°C (104°F), you can turn on the heat by:

1. Using a thermostat to set the desired temperature.

2. Turning on a space heater or other heating device.

3. Adjusting your HVAC system settings if applicable.This is the same reason I'm having the turn_on_heat tool return

that the heat is on. Without that I was seeing the model turn on the

heat and then tell you it didn't know what to do, like so:

User> Use the available tools to find out the current temperature in the living room and use the right tool to turn on the heat if it is under 40 Celsius.

+++ Calling tool 'read_temperature' with arguments {"location":"living room"}

--> "25"

+++ Calling tool 'turn_on_heat' with arguments {}

--> ""

Agent> I don't have access to external tools or devices, so I can't directly check the temperature in your living room or control any heating systems. However, I can guide you on how to do this:

1. **Check the Temperature:**

- Use a smart thermostat or a smart home device that can monitor the temperature.

- Alternatively, use a smartphone app connected to a smart thermostat.

2. **Turn On the Heat:**

- If the temperature is below 40°C (104°F), you can use the same smart thermostat or smart home device to turn on the heat.

- Ensure that your heating system is compatible with smart controls and follow the manufacturer's instructions for operation.

If you provide more details about the devices you have, I can give more specific guidance.These results also aren't totally reliable (LLMs usually do not have deterministic behavior) so if you try this yourself you may need to run the program a couple of times to get the desired result. You'd probably get a better result if you were using a smarter model, but I picked something that would run well on low-end machines, because the next thing I want to do is go a level deeper into what's actually going on, and that requires a modal I can run locally.

Internals #

As I said above we're using the Ollama API rather than a local library so that you can see the actual data we're sending to the API, but that's just the first layer of the onion because each LLM has its own idiosyncratic syntax which Ollama translates to and from. For example, here are is what our initial shirt prompt turns into when we send it to Mistral and Gemma (one of Google's open weight models) respectively:[4]

Mistral #

[SYSTEM_PROMPT]You are Mistral Small 3, a Large Language Model (LLM) created by Mistral AI, a French startup headquartered in Paris. Your knowledge base was last updated on 2023-10-01. When you're not sure about some information, you say that you don't have the information and don't make up anything. If the user's question is not clear, ambiguous, or does not provide enough context for you to accurately answer the question, you do not try to answer it right away and you rather ask the user to clarify their request (e.g. \"What are some good restaurants around me?\" => \"Where are you?\" or \"When is the next flight to Tokyo\" => \"Where do you travel from?\")[/SYSTEM_PROMPT][INST]My shirt is blue[/INST]Gemma #

<start_of_turn>user\nMy shirt is blue<end_of_turn>\n<start_of_turn>modelThis is, as they say, a "rich text". The first thing to notice is that neither of these prompts is JSON. Instead, Ollama has taken our JSON API input and translated it into this stuff, which we'll generously call "structured". However, each model has made its own idiosyncratic choices:

-

Mistral uses something that kind of looks like XML if you globally replaced every angle bracket with a square bracket. Gemma uses XML syntax.[5] As we'll see shortly, OpenAI's models use something even goofier, with tags like

<|start|>and<|end|>. -

Mistral includes a system prompt that tries to set some basic ground rules, whereas with Gemma you're on your own.

All this is just hidden by Ollama, which has a pretty fancy templating engine that lets each downloadable model specify how to translate to and from the Ollama API to the model-specific stuff.

I think the coolest thing here, though, is what's at the end of the Gemma prompt, which is basically an incomplete response from the model's response, with just the framing ready for the model to fill it in. What's going on here? Well, recall that an LLM is basically a completion machine, and it's trying to continue the conversation, so basically we're telling the model "the next thing that's going to happen in this conversation is that the model is going to say something". OpenAI's open models do the same thing. Here's gpt-oss-20b:

<|start|>system<|message|>You are ChatGPT, a large language model trained by OpenAI.\nKnowledge cutoff: 2024-06\nCurrent date: 2026-03-04\n\nReasoning: medium\n\n# Valid channels: analysis, commentary, final. Channel must be included for every message.<|end|><|start|>user<|message|>My shirt is blue<|end|><|start|>assistantThe responses from Mistral and Gemma are about what you would expect:

Mistral #

That's a nice color! Do you need help with something related to your shirt, or would you like to talk about something else?Gemma #

That's cool! Blue is a great color for a shirt. 😊 \n\nIs it a light blue, a dark blue, or somewhere in between? Do you like wearing blue?\n\n\n\nThere don't seem to be any delimiters here, so this could be a bug in my instrumentation, but I think that's actually what's going on.[6]

Now take a look at what gpt-oss looks like:

<|channel|>analysis<|message|>We need to respond appropriately. The user says \"My shirt is blue\". It's a statement. We can respond with empathy or ask about context. Might be a conversation about shirts, colors, etc. We can ask what they like about blue shirts, or what occasion. Provide a playful or helpful answer. Keep tone friendly. Also check guidelines. There's no policy violation. Provide short, friendly reply.\n\nWe can ask: \"Cool! Is it a casual or formal shirt? Do you like the shade of blue?\" Let's produce.<|end|><|start|>assistant<|channel|>final<|message|>Nice! Blue is a classic choice. Is it a casual tee, a dress shirt, or something else? And which shade do you like—navy, sky blue, or maybe a bright cobalt?This is really cool, because we're actually now getting two kinds of output:

- The content we asked for (i.e., the model's response)

- The thinking behind the answer

This is an important clue to what's actually going on under the hood. Reformatting it to make it clearer:[7]

<|channel|>analysis

<|message|>We need to respond appropriately. The user says \"My

shirt is blue\". It's a statement. We can respond with empathy or

ask about context. Might be a conversation about shirts, colors,

etc. We can ask what they like about blue shirts, or what

occasion. Provide a playful or helpful answer. Keep tone

friendly. Also check guidelines. There's no policy

violation. Provide short, friendly reply.\n\nWe can ask: \"Cool!

Is it a casual or formal shirt? Do you like the shade of blue?\"

Let's produce.

<|end|>

<|start|>

assistant

<|channel|>final

<|message|>Nice! Blue is a classic choice. Is it a casual tee, a

dress shirt, or something else? And which shade do you like—navy,

sky blue, or maybe a bright cobalt?What we've got here is a "reasoning" model, and what that means in practice is that it produces its "thinking" process out loud as part of the model output and after that thinking is done ("Let's produce" in the text above) it actually produces the output that's intended for the user. What this output shows, though, is that it's still all text production—albeit with a lot of tuning—basically what's happening the model just produces the reasoning text first and then produces the output that follows—in a literal sense!—from that reasoning.

Tool-Calling #

Now let's ask see when we call a tool. Here's Mistral and gpt-oss after I removed the system prompts (the version of Gemma I'm using didn't want to do tool calling, so I didn't show it, but you can use functiongemma):

Mistral #

[AVAILABLE_TOOLS][{\"type\":\"function\",\"function\":{\"name\":\"read_temperature\",\"description\":\"Return the room temperature in degrees Celsius\",\"parameters\":{\"type\":\"object\",\"required\":[\"location\"],\"properties\":{\"location\":{\"type\":\"string\",\"description\":\"The room name\"}}}}},{\"type\":\"function\",\"function\":{\"name\":\"turn_on_heat\",\"description\":\"Turn on the heat\",\"parameters\":{\"type\":\"object\",\"required\":[\"location\"],\"properties\":{\"location\":{\"type\":\"string\",\"description\":\"The room name\"}}}}}][/AVAILABLE_TOOLS][INST]Use the available tools to find out the current temperature.[/INST]GPT #

<|end|><|start|>developer<|message|># Tools\n\n## functions\n\nnamespace functions {\n\n// Return the room temperature in degrees Celsius\ntype read_temperature = (_: {\n // The room name\n location: string,\n}) => any;\n\n// Turn on the heat\ntype turn_on_heat = (_: {\n // The room name\n location: string,\n}) => any;\n\n} // namespace functions<|end|><|start|>user<|message|>Use the available tools to find out the current temperature.<|end|><|start|>assistantHoly mixture of formats, batman. In both cases we have quasi-XML with embedded

JSON. With Mistral the the JSON is just inlined into the [AVAILABLE_TOOLS] block

and with GPT it's even wackier, and has been turned into some kind of quasi-function notation

and all the quotes stripped (harmony format).[8]

And finally, here's the actual tool calls, which are about what you would expect:

Mistral #

[TOOL_CALLS][{\"name\":\"read_temperature\",\"arguments\":{\"location\": \"living room\"}}]GPT #

<|channel|>analysis<|message|>We need to check: read_temperature returns 25 degrees Celsius. Need to turn on heat if under 40 Celsius. 25 < 40, so we should turn on heat. Use turn_on_heat tool.<|end|><|start|>assistant<|channel|>commentary to=functions.turn_on_heat <|constrain|>json<|message|>{\"location\":\"living room\"}Don't ask me why the GPT tool calls are in the commentary channel. That's just how things are.

Model Context Protocol #

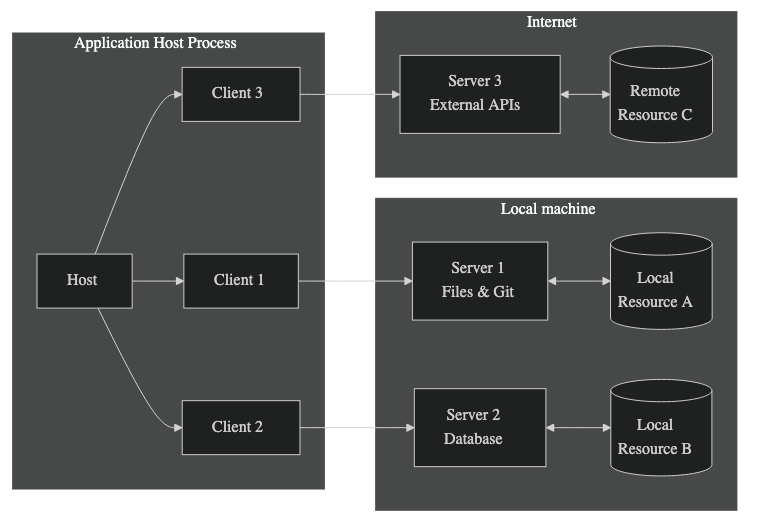

Tools aren't the only way that an AI model can interact with the outside world. For example, Anthropic has developed something called the Model Context Protocol (MCP), which is a way for models to interact with external resources (tools, data, etc.).

MCP Architecture: from modelcontextprotocol.io[9]

The arrows connecting the host process and the servers are MCP, which is a fairly simple JSON-RPC protocol. Like tool calling, MCP is generic in that it specifies how to talk to external resources but doesn't specify any details about the resources themselves. Instead, the servers are responsible for providing descriptions of the resources, which can currently be any of:

- prompts

- e.g.,

code_review <code> - Resources

- such as access to static files, Git repos, etc.

- Tools

- just like we've seen these already

The client can interrogate the server to learn about each of these resource, which come packaged in convenient descriptions just like we saw with tools. For instance, here is an example tool description from the MCP spec:

{

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"id": 1,

"result": {

"tools": [

{

"name": "get_weather",

"title": "Weather Information Provider",

"description": "Get current weather information for a location",

"inputSchema": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"location": {

"type": "string",

"description": "City name or zip code"

}

},

"required": ["location"]

},

"icons": [

{

"src": "https://example.com/weather-icon.png",

"mimeType": "image/png",

"sizes": ["48x48"]

}

]

}

],

"nextCursor": "next-page-cursor"

}

}This should look incredibly familiar, because it's basically

the same thing as you would feed in for a tool description

with Ollama. This is actually the tool description

format

that Claude uses, where things are named a little differently

(e.g., inputSchema instead of properties), but if you

can read one you can read the other.[10]

The situation is roughly similar for the descriptions

for prompts and resources.

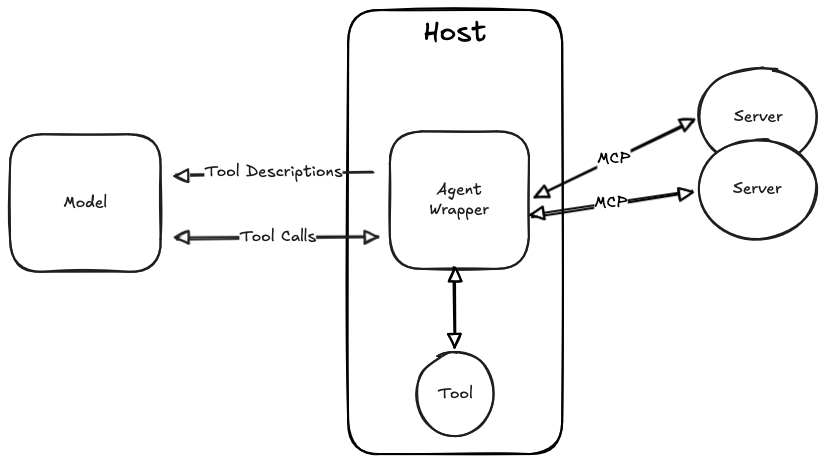

It's important to realize that using server-side resources via MCP is isomorphic to tool calling. Recall that the model doesn't know how the tools are implemented, it just knows that they exist. This means that if you have an LLM which knows how to call tools, you can make it do MCP just by creating a translation layer that exposes the MCP-provided tools as if they were regular tools, as shown below:

In this diagram, we actually have three sources of tools, namely the two MCP servers and then a local tool. The agent wrapper just collects all the tools and provides them to the LLM without distinguishing where they live, and then is responsible for dispatching the tool requests to wherever they need to go. You can handle resource requests the same way, with the resource just being a specialized kind of tool that reads static data. Prompts are a little different, and I'm not going to handle them here.

Server to Client #

There is a bit more to MCP than this. In particular, MCP includes functions to let the server ask the client to access the LLM on its behalf (e.g., ask for completion). However, these too don't require anything new from the model, but are just implemented in the wrapper code, which accesses the model on the user's behalf.

The important thing to realize here is that the LLM doesn't need to know anything about MCP at all, because this part of MCP is just tool calling wearing a different hat. As long as it's set up for tool calling, which has a simple request/response model, we can do all the translation to MCP in the deterministic agent wrapper code (which doesn't require any model tooling). If someone invented a new version of MCP with totally different syntax, we wouldn't need to change the LLM at all, just update the wrapper.

The Bigger Picture #

The amazing thing is really how much we are doing with how little. Our final agent program is less than 350 lines, and though we'd obviously need proper error handling, etc. the functionality here is actually the core of a real agentic tool. We get that power by composing a bunch of simple components:

- An LLM which is able to generate new text in response to a prompt.

- A wrapper which is able to iteratively take in input and then ask the LLM "Given what's happened so far, what's next?"

- A bunch of tools which are able to have effects in the the real world when told to do so by the LLM.

That's all there is.

Using it for real work would mostly consist of (1) adding a full suite of tools and (2) using it with a good model rather than the local ones we're using here. (2) is actually quite straightforward with Ollama actually supports cloud models, translating to the cloud APIs instead of to the local model interfaces. This leaves us with the tools, but the tools aren't about AI, they're just the same kinds of APIs that you'd write for any programming task.

What makes all this possible is that while the models are trained to use tools generically, they aren't trained to use any specific tools. That means that all you have to do to add new capabilities is to write new tools and tell the model about them. The model can than work forward from your instructions and the tools it knows about in order to figure out what tools it needs to call and in what order so that it can accomplish whatever it is you asked it to do.[11]

This setup gives us two avenues for increasing the power of the system. First, we can make the model smarter so it's better at figuring what to do with the tools it has. We saw that already above, where we had to remind the model that it had tools available, but with a better model that wouldn't be necessary. Second, we can give the model model more tools to work with. These avenues are independent but work together: you can make your existing AI-based system better by adding more tools, but then if you replace your model with a smarter one, it will instantly get better with the tools it has.

The model itself is just data, consisting of a model topology and a lot of model weights (i.e., numbers), so you need some software to execute the model, which is what Ollama is. ↩︎

It's obviously a lot of effort to tune the model to generate plausible chat, but that's not our problem right now. ↩︎

Thanks to Gemini for some help with this. ↩︎

I had to instrument Ollama to get it to print this out. ↩︎

Note that these strings should be translated directly into tokens when processed by the model ↩︎

All these extra

\ns are real serial killer stuff. ↩︎I didn't screw up the indentation. Remember what I said earlier about how the prompt includes the start of the model's response? Well that's the missing part, which goes

<|start|>assistant. ↩︎This is a whole other topic, but if you're familiar with how quoting issues can lead to stuff like SQL injection, you're quite likely huddled up in a ball sobbing by now. There is indeed an analog to SQL injection in LLMs called prompt injection which will most likely be the subject of a future post. ↩︎

The official SVG on the site had a little hovering navigation tool on it, so I had to cut out the SVG and rerender it in my browser and I was too lazy to get their CSS working. ↩︎

It's actually an interesting question whether you could feed one style of description to another kind of model and have it work. Remember that at the end of the day you're just passing text to the LLM, so it's quite possible the model is smart enough to figure it out, just as you can, though you'd probably have to work around the various layers of structure in the API that expect properly formatted JSON. ↩︎

This is of course basically the same task as software engineering. ↩︎