Privacy for Genetic Genealogy: Happy Goldfish Bowl Everyone

Posted by ekr on 02 Jan 2022

The combination of "consumer genetics" (CG) in the form of widespread cheap genetic testing and crowdsourced genealogical DNA databases like GEDmatch has opened up whole new possibilities in the use of genetic data. One of these is that you can often identify—or at least partially identify—the source of an unknown DNA sample based on known samples voluntarily submitted by their relatives. This has obvious applications for criminal investigation, as described in a recent article in the New York Times.

This is something I've been expecting for some time, ever since widespread cheap DNA analysis became available. It doesn't even require sequencing, which is still somewhat expensive (on the order of $1000) but rather a much cheaper technique that just looks at specific sites, where there is known to be variation in single base pairs, so-called Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). You can then use technologies like DNA microarrays to examine those regions.

The way this works is that there are a number of Direct To Consumer (DTC) genetic testing companies like AncestryDNA and tellmeGen which will analyze your DNA from a sample (typically saliva) and give you a digital file with the information. This costs about $100 US. You can then upload that data to one of a number of databases designed for genealogical applications, such as GEDmatch, which let you compare the sample you uploaded to that of other people. This lets you see who is closely related (and potentially on which side of the family (because of genes which appear on only the X or Y chromosome) and gradually build up at least a partial family tree for the submitted sample.

The advertised purpose for this kind of database is to tell people about their ethnic heritage, help them find unknown relatives, etc. but of course there are obvious law enforcement applications. Most famously, genealogical DNA analysis was used to identify the Golden State Killer, but the main subject of the NYT piece, CeCe Moore, has also solved a number of other cold cases using DNA-based techniques. This all seemed to be being done on a sort of ad hoc basis without a lot of thought given to the bigger picture when suddenly there was a lot of public attention and the genealogy sites had to quickly figure out the broader implications:

Two days later, GEDmatch became all but useless to Moore.

Following the Golden State Killer arrest, in 2018, the site had posted a warning to users that police were uploading profiles, and hastily instituted a policy restricting such use to homicides, sexual assaults and unidentified bodies. But a few weeks before the Idaho Falls announcement, it emerged that one of the site’s founder-operators had, in a somewhat naïve, grandfatherly way, made an exception for a detective in Utah investigating a recent attempted murder. Moore was the one tasked with identifying the suspect (and did). Around the same time, it also emerged that FamilyTreeDNA, a consumer site with more than two million users, had been discreetly allowing the F.B.I. to upload suspect profiles to its database for genetic-genealogy searches.

GEDmatch scrambled to opt all accounts out of law-enforcement searches by default. Overnight, Moore’s available matches went from over a million profiles to zero, and her ability to work new cases practically vanished. “People will die,” she told CNN. In the months that followed, the handful of genetic genealogists whom she had recruited to build out the Parabon team had their hours cut, and she spent most of her time toiling on old cases for which she already had the list of matches.

This is a pretty common pattern with technologies with privacy implications, which is that the impact on privacy depends strongly on scale; the impact is small when DNA analysis costs tens of thousands of dollars and we only have a few samples, but as technology—both collection technology and processing technology—improves, we have a situation where mass surveillance becomes not just possible but cheap. Other situations where we can see this happening are automatic license plate readers, face recognition, and doorbell cameras.

How effective is genetic genealogy? #

Using one of these databases, it is quite cheap and effective to partially identify someone from their DNA sample. Ehrlich et al. report that if you have a sample of 2% of the population it will be possible to find a third cousin for 99% of the population and a second cousin for 65% of the population. When combined with actual genealogical data, this gives you a set of potential people the sample could have come from. The NYT (and Ehrlich) describe a time consuming manual process for narrowing things down a specific individual, but this seems like the kind of thing that specialized software would make easier, and of course the more samples you have, the better it will work.

The process of collecting the samples and populating the database is also fairly cheap, but more importantly, the person doing the investigation doesn't have to pay that cost because people are doing it voluntarily. They only have to pay the cost for the unknown sample they want to target, but we're talking about $100 for a sample kit. They also have to collect that sample, but—and here's the part that should make you nervous—they don't really need the subject's cooperation for this. The NYT article mentions two specific cases, one in which the suspect "spit out his chewing gum on a bike ride" and another in which the suspect "momentarily opened the door of his semi truck to reach around behind the cab, and let fall a coffee cup with DNA".

This sort of data collection is well within the reach of ordinary people, not just law enforcement. If the target leaves a coffee cup in the trash or a cigarette butt on the ground, anyone can potentially pick it up and identify them using exactly these techniques, and once they have the target's name, they are in a position to violate their privacy in other ways. It's actually easier in this case than in the criminal "unknown sample" cases because if you have seen the person and so once you have candidate names, you can narrow it down by their appearance.

How to provide privacy? #

This kind of data has a number of features that seem to make it very hard to keep private using the usual techniques we think about:

-

The privacy issue isn't created by the collection of your data but by the collection of other people's data.[1] This makes it more difficult to protect your own privacy. For instance, it's not enough to have my own sample be opted out of research applications, I have to have all my relatives samples protected as well. In order to protect myself, I have to make sure nobody else can collect my DNA data, which, as we saw above, is pretty difficult.

-

The intended use case and the adversarial use case are basically the same. In many data privacy situations, the object of your analysis isn't privacy sensitive, but the data itself is. In these cases, there are technical approaches to let you analyze the data without taking the risk of exposing the source data. However, for this data, one of the main use cases, is to find close matches, which is precisely what you need in order to re-identify someone. This makes it hard to build effective technical controls without significantly reducing the available system functionality.

At the end of the day, it seems likely that effectively providing privacy for this kind of data will require new legal policies. However, I have seen two proposed sets of (semi)-technical controls that consumer genetics companies might apply to help reduce privacy risk posed by their systems: (1) limiting law enforcement access and (2) requiring that the samples be validated.

Limiting Access By Law Enforcement #

The first, approach, as mentioned in the NYT article, is to limit the use of the data specifically by law enforcement, specifically by requiring a separate opt-in for this use (see Skeva, Laruseau, and Shabani for a review of various company's practices). This seems like an understandable first step by the sites themselves in the face of negative PR, but not really a long term solution, for several reasons. First, a blanket policy like this seems like a poor match for many people's intuition that law enforcement should have access in some cases but not others. One might imagine thinking that the police should be able to do a DNA search for murder but not jay-walking (as described above, GEDmatch originally had a policy of only providing law enforcement access for certain crimes), and perhaps only after they had exhausted other avenues, but it's pretty hard to ask people in what particular cases they want their data to be used to investigate third parties.

Second, it's not clear how much privacy this kind of policy provides; depending on the legal environment in a given jurisdiction, law enforcement may simply be able to compel acess, regardless of the sites policies.[2] Skeva, Laruseau, and Shabani note that many companies have policies that state that they will comply with valid legal process. Even if it were the case that law enforcement couldn't compel access by these their party sites, increasingly law enforcement is gathering its own DNA samples on arrest, and of course these are not subject to site policies. More on this below.

Finally this doesn't address non law-enforcement applications like stalking. Even if we assume you can identify law enforcement users—and what stops them from lying?—the purpose of this kind of system is to allow ordinary people to look up their own genealogy, and it's not like you can tell which ordinary people are actually stalkers.

Requiring Validated Samples #

Ehrlich et al. propose a different approach, which is to restrict who can insert a sample into the system. The way that these systems typically work is that the user uploads a digital genetic data file (GDF) to the genealogy site and can then search based on this file. At present is no technical mechanism to enforce that this is the uploader's own DNA and so they can just collect DNA, sequence it, and upload the result. Ehrlich et al. suggest that the sites refuse to accept sequences that don't come from DTC testing companies (enforced by having the DTC company digitally sign the GDF). This would prevent attacks where you sequenced someone's DNA and just uploaded the sequence.

These policies wouldn't directly enforce that someone had given consent for their sample to be uploaded, because the DTC genetics company doesn't know whose sample belongs to who. Presumably the theory would be that it would be hard to surreptitiously gather a high quality sample from someone and the DTC companies wouldn't be able—or would refuse to—analyze the kind of incidental samples that it was easy to gather from cast-off coffee cups, used gum, etc, so it would be hard to submit someone else's sample. I don't know how true this is actually is; the tests often use saliva and I imagine some kinds of contaminated samples can be analyzed just fine and some cannot be. Of course, a really sophisticated attacker might be able to sequence the sample themselves and then synthesize the relevant regions but we're probably at least a few years away from that being the kind of thing that your average person can do.[3] And of course, this requires you to trust that every DTC company will dutifully enforce policies designed to prevent third party samples.

Of course, this still doesn't address the situation where law enforcement requires the genealogy site to cooperate, as they can present the file in any form that they want.

Other Attacks #

I've focused here almost entirely on identification attacks, as they are the most obvious way to abuse this kind of system. However, Ney, Ceze, and Kohno have shown that it is possible to use the GEDmatch database to extract detailed information about people's DNA. They write:

We were primarily interested in understanding privacy risks to users that had their kits set to the default “Public” privacy setting on GEDmatch. This setting provides the most functionality and allows kits to appear in the results of relative matching queries from other users (but is not supposed to reveal any raw genetic information)

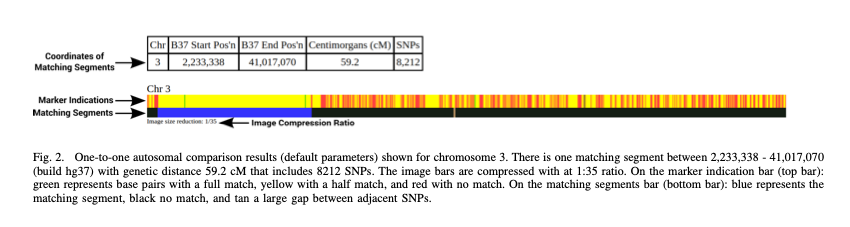

GEDmatch allows you to do a "one-to-one match" in which you compare your sample to a target's sample. The result is a visual comparison, as shown below:

Based on this information, they show that it's possible to extract a the actual value (in some cases) or an estimate (in others) of the the target's genotype for the given SNIP areas, which is far from ideal. They suggest some countermeasures—including the signed upload scheme described above—and limiting the use of the matching APIs.

Law Enforcement Databases #

Most of the discussion above is about how to restrict access to consumer databases, but nothing stops law enforcement from just making their own databases, which is exactly what they are doing. A common practice is just to take DNA samples from people when they are arrested. The report I link to above says there were over 10 million such profiles in the US in 2013, so presumably there are many more now. Such a database seems like it is more effective than a consumer database in some ways and less in others: It's more effective—and hence more of a privacy threat—for communities with high arrest rates because many people will thus be sampled. It's less effective in communities which have low arrest rates.

At present, it appears that the consumer databases are superior just because they are more technically advanced. Historically the federal government has collected only a limited number (13-20) of markers, rather than the more detailed data that people now collect. For this reason, they actually go to consumer genetics sites. The current US DOJ policy on this restricts investigators somewhat, limiting the use to various kinds of violent crimes (or, in some cases, "attempts to commit violent crimes") and requiring that they "must have pursued reasonable investigative leads to solve the case or to identify the unidentified human remains."

Regardless of the current situation, if law enforcement is regularly collecting DNA from suspects, it's only a matter of time before they have more detailed data from that data collection—or at least from new data collection. This data will not be subject to whatever policies consumer genetics sites have; in particular any technical controls that are intended to restrict access to the actual person whose sample it is will not be effective.

What kind of policies might we have? #

People with more policy expertise than me have spent real time on this, so I don't propose to provide a full analysis on potential policy responses. However, it seems like there are really two questions here:

-

How do we prevent abuse of this kind of data for stalking and disclosure of personal information to the public?

-

How do we prevent abuse of this kind of data by law enforcement?

The first of these questions seems like it potentially may have a set of technical solutions: restrict the use of the service to people's own samples and limit the API so it's not possible to learn too much about other people. Neither of these limits is perfect, but they seem like they probably significantly increase the cost of attack and it's probably possible to add additional defenses over time.

The law enforcement question is more difficult, in part because there are going to be strong differences of opinion about how to balance privacy against law enforcement effectiveness (and about how much these techniques make law enforcement more effective). With that said, I suspect that many people do not want law enforcement to be able to use DNA evidence to identify anybody for any reason (and potentially to add them to their database once identified, to make future identification easier); the DOJ policy, for instance, would not allow this. This kind of mass surveillance seems like it will eventually be technically possible—if it isn't already—so if we don't want it, we need a policy response.

From a technical perspective, it seems like there are three main policy approaches:

-

Limit law enforcement's ability to gather DNA samples. In order to use someone's DNA you have to first get it. The government can of course compel you to supply a sample with a warrant, but as noted above, it's also possible to just wait around until you discard something that has your DNA on it. Traditionally trash has been seen as discarded and therefore fair game, but the wide availability of DNA analysis technology seems like it changes the balance.[4] One approach, as Alexia Ramirez from the ACLU proposes,is to require law enforcement to get a warrant to collect your DNA.

-

Limit the investigative use of DNA data. Of course, not all data is collected from identifiable individuals—for instance it might come from a crime scene—and much of the attention so far has been instead on limiting the use of DNA data once it's collected. For instance, one could have policies like the US DOJ's which only allow DNA searches for certain crimes and after other avenues have been exhausted. These policies could of course be made to apply to both consumer and government databases.

-

Limit the retention of samples. There has also been quite a bit of discussion of limiting the government's ability to collect and retain DNA evidence from arrestees. Of course, this would still leave the CG platforms, but would still be a meaningful restriction in that it (1) makes it harder for make it harder for law enforcement to surreptitiously violate policies and (2) gives CG platforms the ability to allow for searches only when legally compelled—though they may of course choose not to do so—rather than when legally allowed.

As I said above, I don't propose to provide any kind of complete policy analysis here. For more, see Jen King and Natalie Ram (1 2).

Summary #

Stepping back from this particular case, this is just one instance of a general trend where your privacy is protected not by infeasibility but rather by inconvenience; it's always been possible for people to follow you around and see everything you do[5], but it was just too hard to do at scale. Technology changes that, both by permitting you to see what you previously couldn't (DNA, thermal imaging) and by making it much cheaper to do at scale, either directly or—as here—by crowdsourcing. Happy goldfish bowl, everyone.[6]

See Jen King on people's perceptions of the implications of submitting their data. ↩︎

See Natalie Ram on the legal situation in the US. ↩︎

Update: 2022-01-02 If/when it does become the case that ordinary people can afford to buy full sequencing equipment—or even when it's down to the place where it's widely available—we're all going to be in some serious trouble because it means that anyone who gets their hands on your used coffee cup will be able to determine precisely what genetic conditions you have, as well as anything else we've managed to work out the genetics for. Right now, we can hope that your average reputable lab won't take such an obviously nonconensual sample, but if you can buy a sequencer for a few hundred thousand dollars, then there are going to be a lot of disreputable labs. ↩︎

At least in the US, there is precedent for requiring warrants when technical capabilities make some kinds of search much more effective, as in Riley v. California (cell phone searches) and Kyllo v. US (thermal imaging) ↩︎

See Justice Scalia on "tiny constables" in City of Ontario v. Quon. ↩︎

This line is taken from Isaac Asimov's prescient The Dead Past, in which someone invents a "chronoscope" which can be used to view the past. It's not really that useful for historical research because it can only go back about 150 years, but it's great for surveillance, because you can watch 1 second ago. ↩︎